µCTL: The Microwave-Assisted Evolution of Coal Liquefaction

A detailed analysis of the "Micro Char to Liquid" process by Bionic Laboratories – From nano-particle generation to finished fuel.

The conversion of solid carbon carriers into liquid fuels has been a central goal of the chemical industry for over a century. While historical methods were often uneconomical or technically extremely complex, Bionic Laboratories BLG GmbH presents a technological quantum leap with the µCTL (Micro Char to Liquid) process.

This article sheds light on the chemical background, plant design, process flows, and safety architecture as depicted in current technical documentation.

1. Heritage and Innovation

To understand the significance of the µCTL process, it is worth looking back. In the summer of 1913, Friedrich Bergius invented the process of converting lignin coal into organic fluids under enormous pressure of 150 atm and at a temperature of 450°C. He received the Nobel Prize in 1931 for this achievement in high-pressure hydrogen processing.

The µCTL process picks up on this principle but revolutionizes it by combining it with modern technologies:

- Nano-catalysts: Building on the work of Prof. Dr. Ernst Bayer on catalytic low-temperature depolymerization, special zeolite catalysts are used.

- Microwave technology: Based on Albert Wallace Hull's research on the magnetron, energy is targeted and controlled.

The result is significant: Instead of the historical 150 atm, the µCTL process operates at a reduced hydrogen pressure of 60 to 80 atm. This not only reduces material stress but also increases safety and efficiency.

2. The Core Process: From Solid to Nano-Aerosol

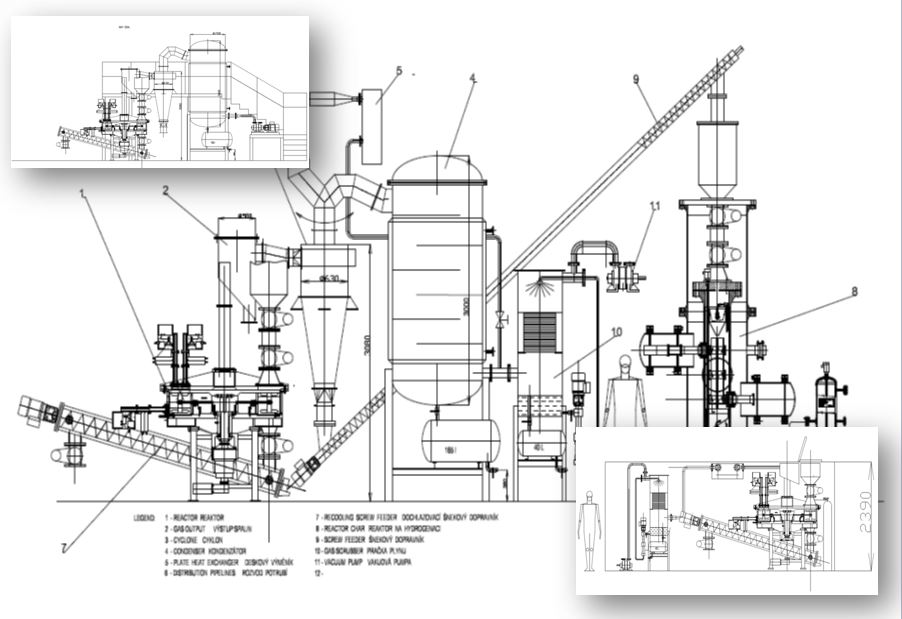

The heart of the technology is the way the feedstock—whether lignite or anthracite—is prepared. In the technical schematics of the plant, this is referred to as the "Microfuel Unit".

Phase 1: Preprocessing

Unprocessed coal is not simply burned or heated. The "Microfuel Unit" first separates the volatile contents and destroys the crystal structure of the coal. The goal is the generation of a nano-carbon aerosol with a particle size of less than 4 nanometers. This extreme comminution enormously maximizes the surface area for the subsequent chemical reaction.

Phase 2: Hydrogenation in the Microwave Field

A look at the plant diagram shows the path of the material:

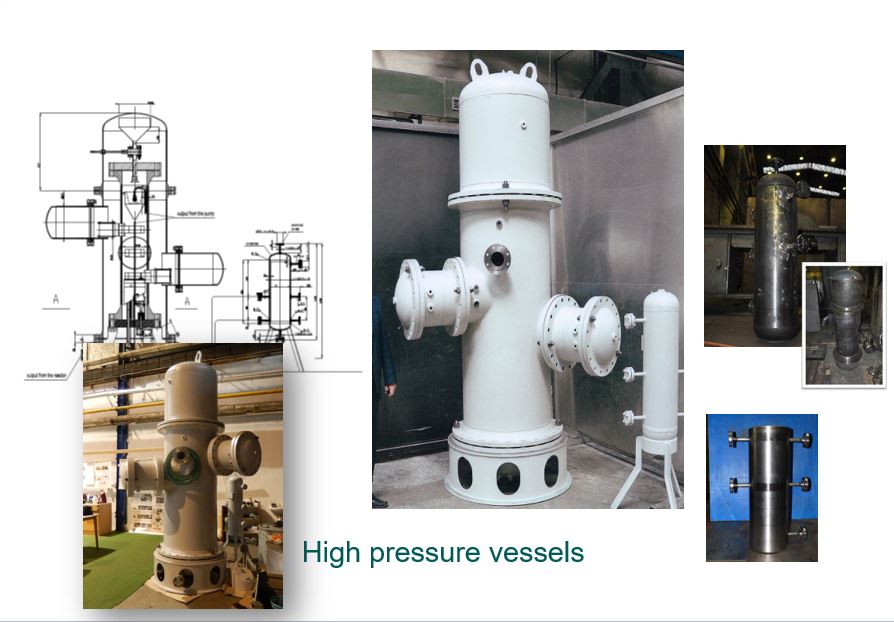

- The nano-aerosol is transported into the high-pressure vessels.

- There, hydrogenation takes place on a catalyst net that is directly heated by microwaves.

- With the addition of hydrogen, hydrocarbons are formed here.

The technical drawing of the reactor unit clarifies that both a low-pressure microwave reactor (for preparation) and a high-pressure microwave reactor (for synthesis) are integrated here.

3. Plant Design and Mass Balance

The efficiency of the plant can be read from the mass balance of a single liquefaction unit. With an input of 1,000 kg of coal per hour (with an energy value of 33 MJ/kg), an additional 110 kg of hydrogen and catalysts as well as heavy oil are required.

The output of this single unit is impressive:

- 520 kg Light Oil: This is the primary product for fuels (gasoline/diesel).

- 698 kg Heavy Oil: This is largely recirculated to support the process.

- 270 kg Gas: A usable by-product.

- 80 kg Residues: The waste portion is comparatively low.

Visualization of the Plant

The side view ("Sideview of processing block") in the documentation gives an impression of the physical dimensions. On the left side is the Microfuel Unit, which separates water and oils from volatile contents via cyclones and condensers. On the right stands the massive high-pressure microwave reactor, where the actual hydrogenation of the coal aerosol takes place.

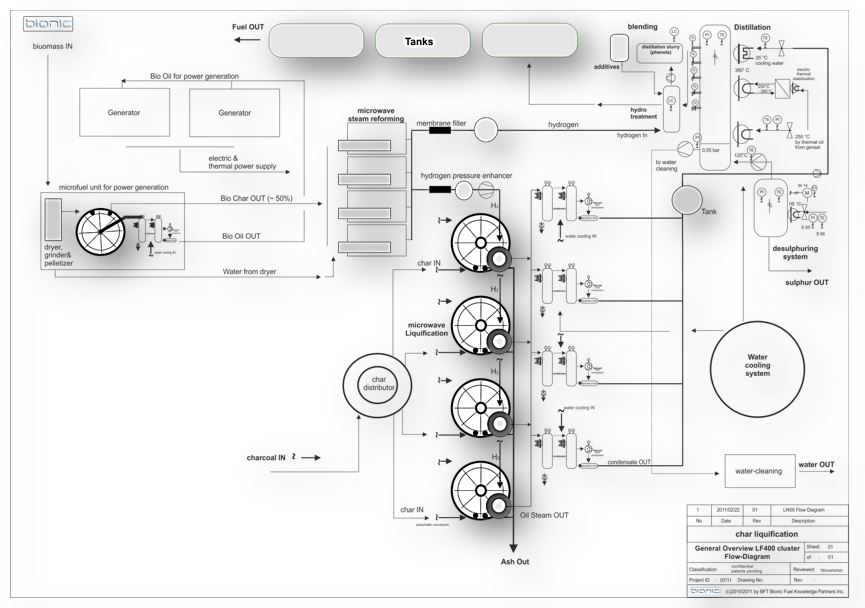

4. The Cluster Concept: Scalability for Industry

For industrial application, the µCTL system is modular. The documentation shows, for example, a 4x4 cluster concept.

- Structure: Four Microfuel units handle the preprocessing of the coal.

- Integration: Attached to these are four hydrogenation units for final liquefaction.

- Centralization: All units feed into a large, central distillation column. Here, light products (fuel) are separated, while heavy by-products are routed back to the high-pressure vessels.

An attached block heat and power plant can directly use the produced bio-oil or gas to provide electrical and thermal energy for the plant's operation (e.g., 24 MWh).

5. Sustainable Hydrogen: The Steam Reformer

A critical point in coal liquefaction is usually the source of the hydrogen. The µCTL process solves this with a microwave-driven biomass steam/shift reformer.

This uses conventional biomass like wood or straw and converts it chemically. Particularly noteworthy is the plasma burner at the end of the process: At temperatures of approx. 4,000°C, it destroys all unwanted volatile products and cleans the gas before it is compressed to 100 bar and fed into the reactors. This reformer completely covers the hydrogen demand of the Microchar facilities.

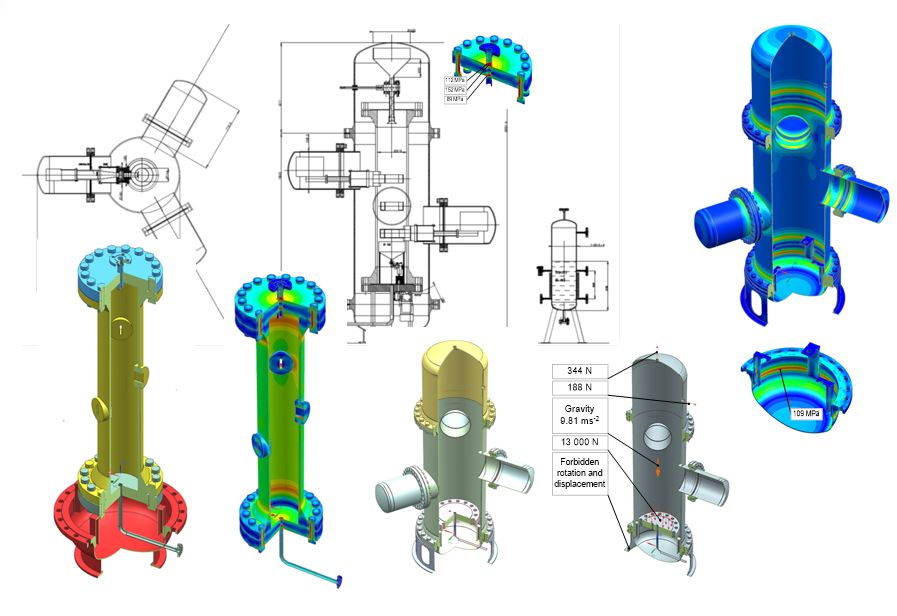

6. Safety via Simulation

Handling hydrogen under high pressure requires maximum safety precautions. The design of the reactors is based on detailed stress analyses conducted by the CVTS (Center of design of forming machines).

The simulations show exactly where material stresses occur to rule out weak points right from the design phase.

Additionally, the plant features extensive protective measures:

- Radiation protection from microwaves via special Faraday cages.

- Double insulation of all oil-containing parts.

- Compliance with ATEX (explosion protection) and ASME standards.

- A secondary emergency process control system.

Strestest of the pressure vessels

Conclusion

The µCTL process by Bionic Laboratories represents a significant evolution in fuel technology. Through the intelligent combination of nanotechnology, microwave physics, and modern plant simulation, coal becomes an efficiently usable source for liquid fuels, with low pressures and internal hydrogen production underscoring the economic viability and sustainability of the process.

.jpg#joomlaImage://local-images/Webpics/slider2/mf60B (3).jpg?width=384&height=288)

.jpg#joomlaImage://local-images/Webpics/slider2/mf90B admas (5).jpg?width=5312&height=2988)

.jpg#joomlaImage://local-images/Webpics/slider2/mf90B admas (9).jpg?width=5312&height=2988)